Currently you don't have any items added to your cart. Select some items then come back here to complete your purchase.

Go to shopMillions of people cannot access basic medical care, clean water, schools or receive the Good News of God’s love, simply because it’s too dangerous or time-consuming to reach them. We provide flights for 1,500 aid, development and mission organisations to enable them to transform lives. It’s a great partnership – and you can help make it possible.

Find out more

We fly light aircraft in more than 25 countries, reaching more communities than any other airline. Discover more about the places where we help meet local needs.

Find out more

Working in partnership with hundreds of other Christian and relief organisations, MAF enables practical help, physical healing and spiritual hope to be delivered to some of the world’s most remote and inaccessible communities.

Find out more

We provide flights for 1,500 aid, development and mission organisations to enable them to transform lives. It’s a great partnership – and you can help make it possible.

Find out more

Here's your place to find out what's going on in the world of MAF. From latest news from around the world to current campaigns and up-coming events.

Find out more

Join us on a journey of Discovery – visit places rarely featured in travel brochures to experience wonderful communities far from the tourist trail.

Find out more

Packed with stories and features about the work we do and the remote areas we reach, you’ll be encouraged and inspired by the many creative ways we bring help, hope and healing to vulnerable and forgotten people in Africa and Asia-Pacific.

Find out more

Great guests. Real stories. Lives transformed. MAF's 'Flying for Life' podcast

Find out moreIf you are a church or religious organisation who would like to share more stories and images about the work of MAF, then in this section you can find ready-written material, prepared by the MAF UK News team, for you to download and use.

Find out more

We believe every community, however remote, should have the essentials for life.

Find out more

Follow MAF's life-transforming adventures and latest developments from around the world…

Find out more

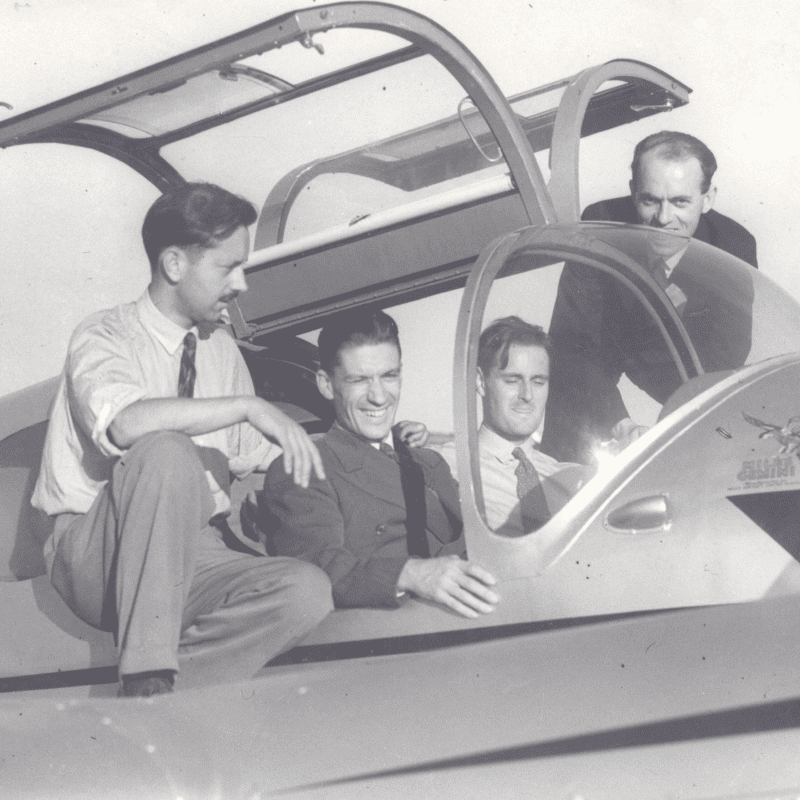

Out of the ashes of World War II came a new movement, which sought to use aviation as a force for good instead of destruction. Inspired by their Christian faith, MAF's founders decided to use their flying and engineering skills to deliver help, hope and healing to the world's most isolated people. 80 years later, their legacy lives on...

Find out more

When it comes to reaching the most isolated people, MAF needs the best tools for the job. Discover the difference the right aircraft can make to MAF’s mission.

Find out more

MAF provides a subsidised flight service to over 2000 relief and mission groups so they can bring help, hope and healing to the world’s isolated people in need. Gifts from people like you make this possible

Find out more

The MAF annual report outlines the key impacts and outcomes of our work and presents some examples from our operations to illustrate these.

Find out more

At the heart of all we do is a desire to see isolated people changed by the love of Christ. Become an MAF Prayer Partner and be a vital part of our team. Partner with us in prayer today!

Find out more

Do you have a heart for mission and want to get involved in the work of MAF? If so why not consider joining our UK and Ireland volunteer teams.

Find out more

Browse our menu of resources and find out how MAF can help resource you, your church, your school or your group, to help raise awareness of people living in some of the remotest areas on earth.

Find out more

Find out more about our staff serving overseas with MAF and how you can support them.

Find out more

Join us and support some of the most unreachable people on earth. Together, we can bring help, hope and healing to isolated people in need.

Find out more

Explore our range of MAF merch from books and bags to socks, t-shirts and hoodies. Plus so much more!

Find out more

What’s involved in working overseas for the world’s largest humanitarian air service?

Find out more

For over 75 years MAF has been bringing help, hope and healing to the remote communities of the world. Pilots, engineers, managers, IT technicians, teachers, administrators and many other professionals have come together to bring transformation to remote communities.

Find out more

Answers to some of the most common and important questions about working with MAF.

Find out more

Come us find us at various events around the UK this year. We'd love to meet you and tell you more about the amazing opportunities to train and work with us.

Find out more

We are seeking to enable aspiring aircraft maintenance engineers to join MAF and work overseas. If you’re successful, we will help you achieve the theoretical knowledge and practical experience necessary to obtain an EASA B1 or B2 licence. You will then go on to serve with MAF in various programmes across Africa and the Asia-Pacific region.

Find out more

Have you got what it takes? If you’re successful, we will help you achieve the theoretical knowledge and practical experience necessary to obtain a Commercial Pilots Licence and a Command Instrument Rating. You will then go on to serve in an MAF programme in either the Africa or Asia-Pacific region.

Find out more

Over the years, hundreds of men and women have answered God’s call and set off on the adventure which is MAF!

Find out more

Help us to tell others about the need for more people to serve with MAF with this selection of recruitment posters

Find out more

The easiest way to give to us is online. Your gift can help us provide support to those in need.

Find out more

Please use this form to update your regular donation amount. Thanks so much.

Find out more

Find out more about our staff serving overseas with MAF and how you can support them.

Find out more

A gift to MAF in your Will can change lives for families, communities and nations.

Find out more

Thank you for choosing to honour your loved one’s memory and celebrate their life by helping some of the most isolated people on earth. We are so grateful for your support at this sad time.

Find out more

Our life-transforming work wouldn’t be possible without the generous support of our corporate partners.

Find out more

Make a difference in real time and give to the things that are most important to you.

Find out more

Explore our range of MAF merch from books and bags to socks, t-shirts and hoodies. Plus so much more!

Find out more

Choose from a range of gifts to bless some of the world's most isolated people.

Find out more

Did you know that MAF collects postcards to raise thousands of pounds for our vital work?

Find out more