Rev Bernard Suwa, Pastor of Grace Community Church in Juba (credit: Bernard Suwa)

In the second episode of MAF’s new Flying for Life podcast ‘No poverty’, we hear from the Rev Bernard Suwa – pastor of Grace Community Church in Juba and former CEO of development charity ACROSS. Bernard chats to Josh Carter about how MAF transformed his life and how aviation is still critical in South Sudan today

Until the age of seven, Bernard Suwa lived peacefully with his parents and four brothers in the village of Arapi in southern Sudan, but in 1964, that all changed.

The first Sudanese Civil War, which broke out in 1955, finally reached his family’s village and they were forced to flee to Uganda. Bernard left with his older married sister Natalia, her husband Ibrahim and their new-born baby Sabina. Bernard’s parents and other siblings would follow later. Bernard recalls that fateful day:

‘We began our journey on foot – about 22 miles to the border of Uganda – but because the main road was already infested with the armies from the north, we had to access the border another way.

‘The only thing I can remember from that journey was crossing the river at the border into Uganda. My brother-in-law put me on his shoulders with his head hanging between my legs, my niece was over his shoulder and his right hand was dragging my sister through the raging waters.’

Rev Bernard Suwa – pastor of Grace Community Church and MAF partner

Bernard and his sister’s family ended up in Gulu, northern Uganda, but his parents and other siblings would settle at another camp in Elegu near the border. Bernard was separated from his parents.

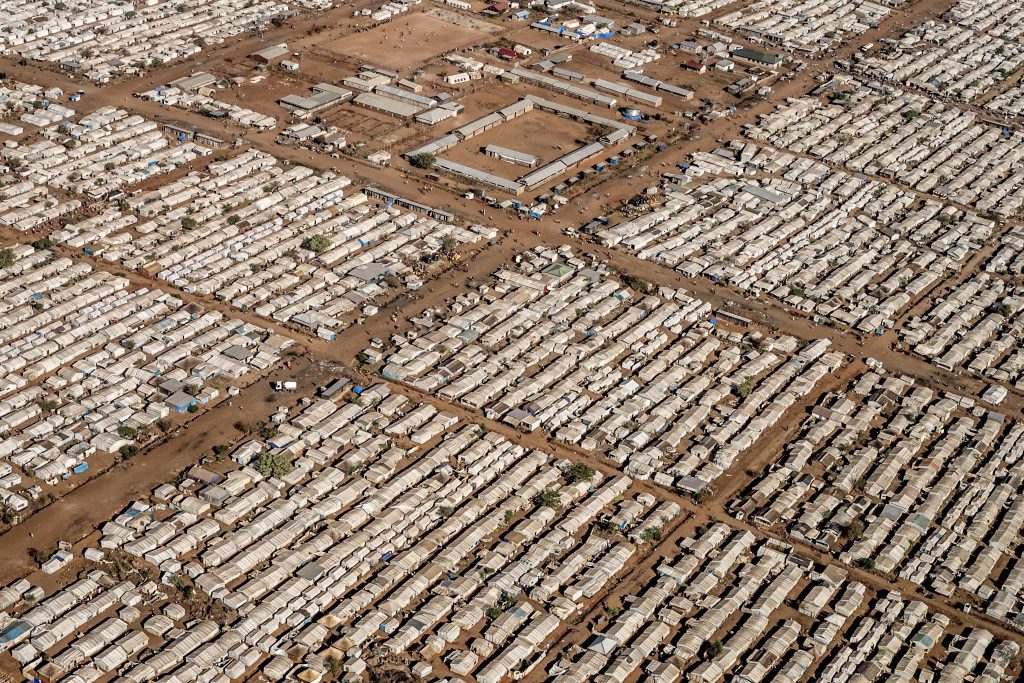

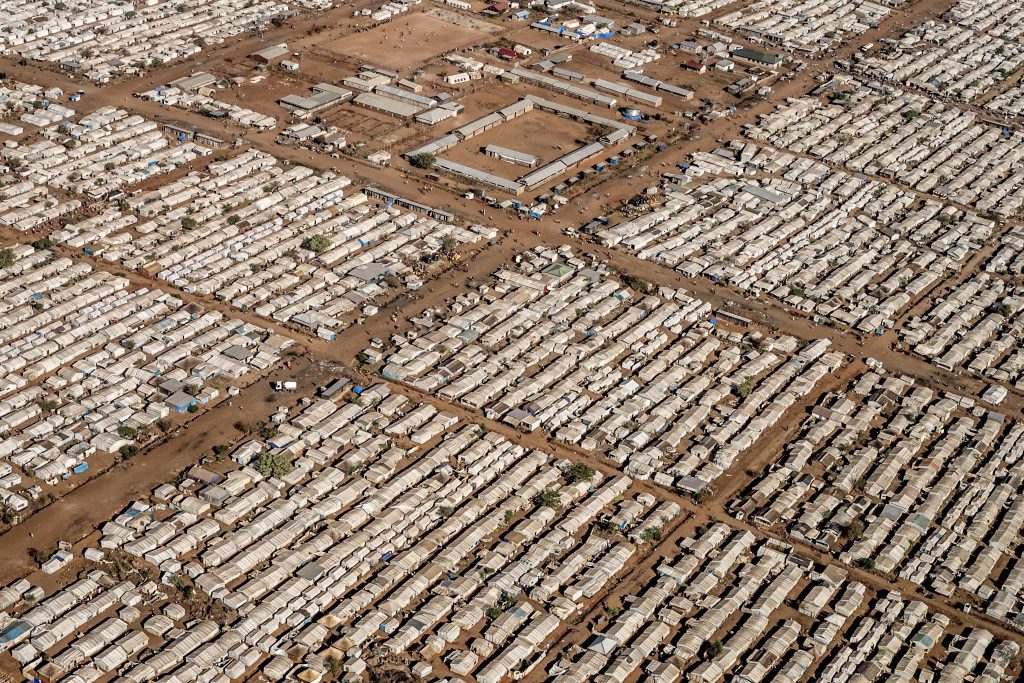

The UN has called the millions of South Sudanese forced to flee their home ‘the biggest refugee crisis in Africa’ (credit: Dave Forney)

Ravages of war

When we see refugee camps on the news today, we are familiar with rows and rows of tents, but when Bernard became a refugee at the tender age of seven, it was a very different scenario:

‘We didn’t have tents. We had settlement areas where we were responsible for constructing our own hut. The Ugandan authorities gave us tools to settle – machetes for cutting wood and grass and a hoe for digging land – that was all we had. We made a grass thatched roof with mud walls and that was it! Tents are relatively modern – not in my time.’

After walking 22 miles to safety, feeling exhausted, frightened and hungry, it’s hard to fathom building your own home but as time would tell, that would be the least of Bernard’s worries.

As refugees in 1964, Bernard’s family had to build a mud hut to live in, similar to these in Arilo, southern South Sudan (credit: Joel Raphael)

In 1970, at the age of 12, Bernard heard the sad news that his father Patricio had died:

‘The Ugandan authorities had decided that refugees living near the border should be moved to another designated refugee camp. The military went from door to door removing refugees.

‘My dad had severe asthma and was unable to leave, but soldiers still bundled him into a lorry to take him away. He died from an asthma attack – that really hit us as a family.’

Due to decades of war, South Sudan has the highest rate of poverty in the world and is bottom of the UN’s Human Development Index (credit: Les Vandenberg)

Today, many orphans live on the streets of South Sudan (credit: Thorkild Jørgensen)

Orphaned as a teenager

The signing of the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement in 1972 ended 17 years of civil war and signalled new hope of returning home. Bernard’s mother Antida – now living at Malamio Camp with 15-year-old Bernard – decided it was time to go home as a family.

Two of Bernard’s brothers, Julius and Adauto, returned to Sudan first to construct huts for the family’s return. Bernard’s job was to look after the family’s possessions at Malamio while Antida sought transport to be repatriated.

Repatriation was very slow, so Antida concluded it would be quicker to walk the 22-mile journey across the border alone. Bernard recounts that tragic day:

‘As she crossed the river from Uganda into Sudan, she fell into the remnants of the military hiding in the bush. They caught up with her and did whatever they wanted to do – probably raped her and left her for dead so that she would not tell her story to the world.

‘My siblings in Sudan thought that my mum was with me and I thought that my mum had already crossed the border and was with my siblings. Two weeks later, we discovered the remains of mum. She was hidden under a bush, which was burnt so that any evidence would be destroyed.

‘Becoming an orphan meant that I didn’t have a proper home. My siblings and I had to fend for ourselves in Juba where I temporarily stayed with my aunt.’

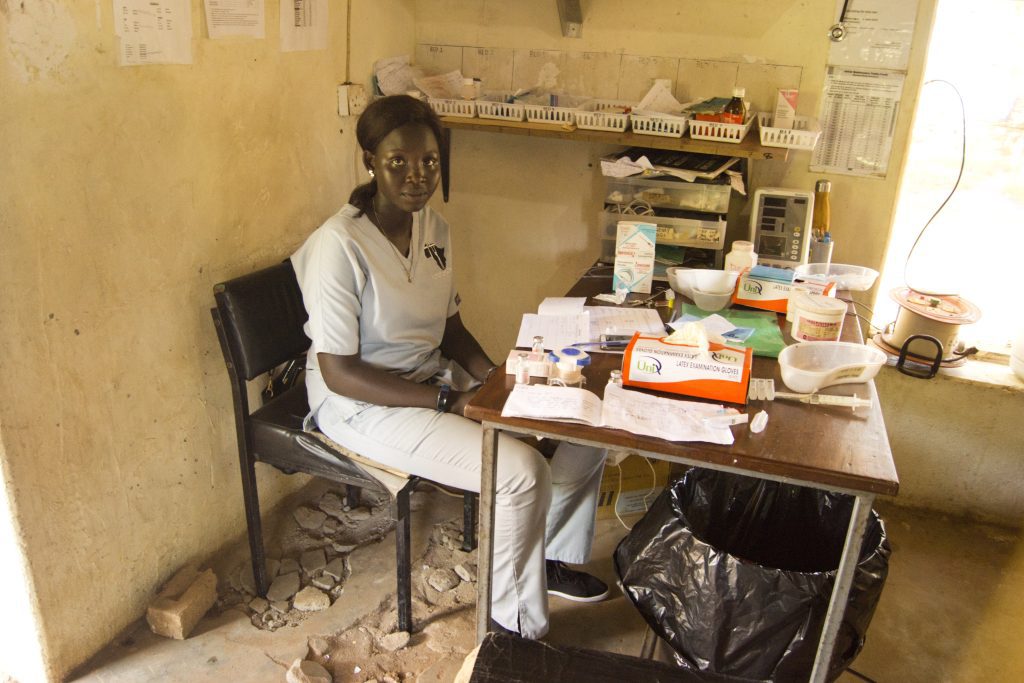

Infrastructure has been badly damaged by war like this clinic in Tonj, western South Sudan (credit: Thorkild Jørgensen)

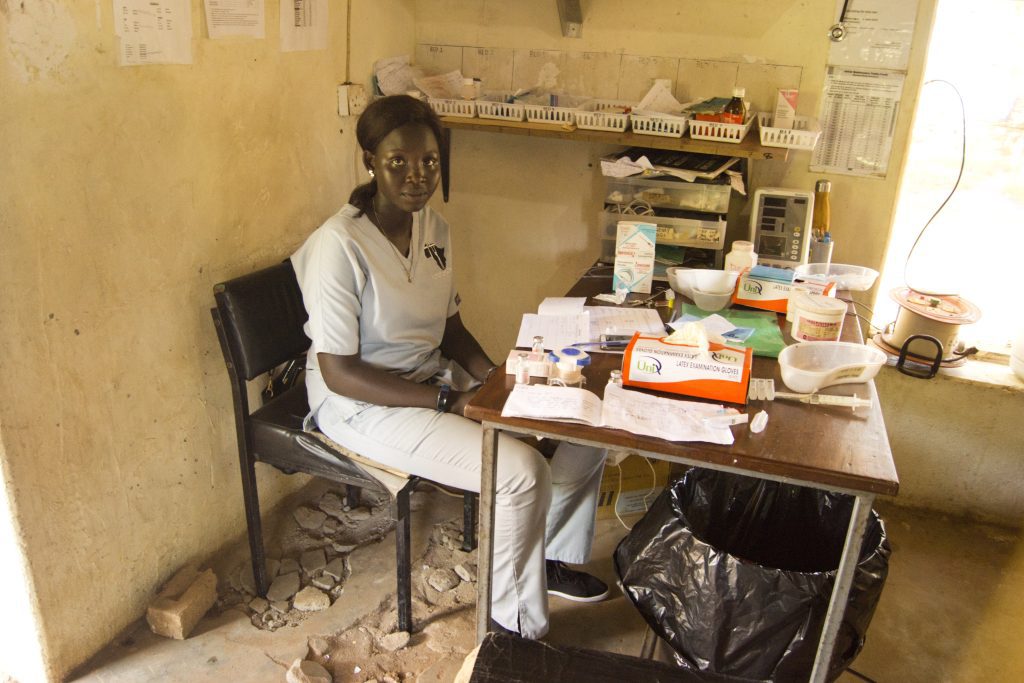

MAF flies organisations like AMREF to remote areas of South Sudan to provide basic healthcare (credit: Thorkild Jørgensen)

‘Life was not worth living any longer’

Now in Juba, Bernard tried to pick up the pieces of his life. He got a free place at Rumbek Secondary School, some 260 miles north of Juba, and threw himself into his studies.

With over 500 students, Bernard felt lost in the crowd. With no home to speak of, he boarded at school during weekends and holidays.

Every Sunday morning, he would sit under the same mango tree in the school grounds wondering why his life had been wrecked by war and poverty:

‘I felt lonely – life wasn’t worth living any longer. One Sunday morning when I was sitting under my mango tree wondering what instrument I would use to take away my life, I heard a song coming from the nearby chapel.

‘They were singing: “What a Friend We Have in Jesus”. When I heard that song for the very first time, I felt that I was being called into that church, so I left my tree, walked in and sang that song with the rest of the students. That was the beginning of my new life. Life was never the same again. I never looked back!’

Little did Bernard know, the chaplain who was leading the service worked for ACROSS – the Christian development charity in Sudan, co-founded by MAF in 1972.

Missionaries from ACROSS adopted Bernard into their Christian family, giving him hope and the much-needed direction he so desperately needed.

Established in 1950, MAF’s oldest African programme has been serving communities like Kapoeta for over 70 years (credit: Jenny Davies)

When roads turn into mud during South Sudan’s 8-month rainy season, MAF is the only way to reach remote areas like Arilo (credit: MAF South Sudan)

God, the anchor

Bernard’s new-found Christian faith may have given him internal peace, but society was once again crumbling into chaos, as Sudan’s second civil war broke out in 1983.

In 1986 at the age of 29, the newly married Bernard, his wife Esther and baby Jennifer, had to flee to Nairobi, Kenya for safety. With international commercial flights closed at Juba Airport, the only way out was with MAF – Bernard’s first flight of many with the charity:

‘ACROSS booked us on a MAF flight. As passengers, we were driven across the border into the Democratic Republic of Congo where we could access MAF flights to Kenya.’

In the safety of Kenya, Bernard studied journalism at Daystar University and graduated in 1990 when ACROSS offered him a publications job in Nairobi, where the charity was forced to relocate:

‘I ended up being recruited by ACROSS – the very organisation that had nurtured me and provided me with my Christian upbringing.’

Bernard worked for ACROSS in Kenya for a number of years boarding many MAF flights to support the development of Sudan.

During this period, he completed a Masters degree in publishing at Scotland’s Stirling University before returning to Kenya in 1994. Bernard also trained as an Anglican Minister, and Joshua and John-Victor were added to his family.

Unfortunately, the Kenyan government refused to extend Bernard’s visa and work permit, so once again the growing family faced an uncertain future.

Fortunately, missionary friends in Australia offered to sponsor the family, so a new life in Sydney awaited them.

‘I slipped into depression’

They migrated to Australia in 2000 and joined a growing Sudanese refugee community. Bernard threw himself into his new life, but many Sudanese refugees struggled with Australian culture.

As their church leader, Bernard supported his community but underestimated the toll it would eventually have on his mental health:

‘There was a lot of domestic violence amongst the Sudanese community, and I was in and out of police stations with various youth problems. I even offered training to police officers about our culture, but by 2004, it was getting too much. That year, I had preached 42 sermons and was flat out.

‘I slipped into depression, but by the time I was offered help from senior church leaders, it was too little, too late – I had broken down. The tragedy is…my wife walked out of our marriage because I was like a vegetable. It took me a year to become human again.’

When Bernard was well enough, he continued his studies by taking up a PhD in education.

Meanwhile, Sudan’s second civil war had ended in 2005 after 22 bloody years. Bernard’s heart was no longer in Australia but once again, God answered prayer:

‘I wanted to leave Sydney and return to Africa to heal because I couldn’t heal in the place where I was wounded. In 2007, ACROSS invited me to take up their chief executive role in Nairobi so I packed my bags!’

Bernard was the CEO of ACROSS from 2007 until 2011, before returning to Juba after 21 years. His family stayed in Australia. His three children and four grandchildren are still there.

Since 2011, Bernard (R) has been supporting missionaries through Grace Community Church (credit: Chris Ball)

Juba – a very different place

At 54, Bernard was finally able to return home. ‘South Sudan’ had gained independence in 2011 but peace didn’t last long. Another brutal civil war marred the world’s newest country from 2013 to 2020.

Today, Juba is a very different place from what Bernard remembers from his youth:

‘Juba was literally just a village when I left. Before the second civil war, insecurity was not a problem. Poor as it was, we could still walk in the middle of the night and nobody would worry you, but now I struggle.

‘I’m torn in two because part of me feels I belong, but as I look at what’s happening, I know things could be done better because of my experience in Scotland and Australia. I belong but don’t belong because I don’t agree with what’s taking place like the lawlessness and aggressiveness on the roads.’

Today, at 66, Bernard finds solace in the ministry that he founded in 2011. ‘Grace Community Church’ in Juba serves overseas missionaries from all over the world as they endeavour to rebuild South Sudan and bring hope to her people:

‘I know there are things that only God can change in my country. My dream is that the war will cease, and political leaders would have a change of heart and put the interests of their people first. I could have gone back to Australia to enjoy my grandchildren, but I think that would be cowardly, because I see the need more clearly here in South Sudan.

‘I thank God for the ministry I have started. Grace Community Church has become a chaplaincy for many MAF and Medair staff, and other Christian organisations. I see my role here as critical and am a firm believer in missionary work in my country. I am very appreciative of the selfless commitment of these people.

‘My encouragement to them is to soldier on. They are not alone. May God who has sent them here continue to look after them and their families. As a product of missionary work myself, I just want to give thanks to God for MAF, which has been in my life for a very long time.’

From medevacs to mobile health clinics, Bernard supports MAF’s far-reaching ministry (credit: Thorkild Jørgensen)

Communities benefit from MAF’s Eastern Equatoria Shuttle service (credit: LuAnne Cadd)

Join Bernard, John Feil – Ops Manager for MAF South Sudan and Peter Claver – Head of Programmes at health charity AMREF for ‘Flying For Life’ – MAF UK’s new podcast, as they discuss tackling poverty in South Sudan.

The Flying for Life podcast is a free resource and part of MAF’s ‘He Saw It Was Good’ Bible Study Series, which explores how Christians can support sustainable development.